An editor for the Roland JX8P. Uses SysEx messages.

Download Size: 57.5 KB Downloads: 2,744

An editor for the Roland JX8P. Uses SysEx messages.

Download Size: 57.5 KB Downloads: 2,744

A panel for the device Voyager by company Moog. Uses high-res parameters for control.

Download Size: 44.4 KB Downloads: 1,475

A simple editor for the Synth Lite 2 synth by the german synth company MFB. It uses CC pairs a special format of MIDI messages, they’re used to gain more resolution.

Download Size: 80.2 KB Downloads: 1,141

It’s a panel for a device “Little Phatty” by company Moog. It uses CCs.

Download Size: 70.3 KB Downloads: 1,933

A simple panel for Roland Juno 106. It does not handle program dumps but editing should work in both directions. Uses SysEx.

Download Size: 412.9 KB Downloads: 4,195

This is a placeholder for all the DEMO panels included in the Ctrlr installation. Those panels showcase some of the features in Ctrlr. Since we often reference them in the forums i thought i’d put them here with a link to the always current version of them (they’re store in a SVN repository so whenever i change something it gets reflected there).

The files are always available here: http://svn.code.sf.net/p/ctrlrv4/code/nightly/Panels/

Here i’ll try to explain how to get started with Ctrlr.

I’ll be using Ctrlr in Standalone mode. What does it mean ? Well if you downloaded Ctrlr there are 2 ways you can run it.

– Standalone, this means you start Ctrlr as any other program in your Operating System (this will be a “.app” on the Mac, a “.exe” on Window and a plain binary on Linux – no extension)

– As a plugin, this means Ctrlr will be loaded as a VST or a AU plugin in your favorite plugin host.

We choose the standalone mode for this tutorial cause we’ll be trying to create something new, the standalone mode gives us more freedom and has less “gotchas” that the Plugin version has. This does not mean you can’t follow this tutorial in the Plugin mode, in reality both versions of Ctrlr share exactly the same code, they’re just run differently, it’s the same code but in a different sandbox.

Let’s start Ctrlr now, after the first start you get an empty window like this:

It isn’t much, first step we’ll do is choose File->New Panel and go on from there, once you do that, a more interesting view presents itself (i overlaid some blue arrows to better explain all parts):

I’ll explain all the elements of the window in detail:

We’ll be making a simple panel to control a synthesizer. For this tutorial we’ll use the Dave Smith Instruments Evolver Desktop synthesizer. This is a great monophonic hybrid synthesizer from Dave Smith. I chose this unit because it uses System Exclusive messages for realtime control of it’s parameters, this is a more complicated way of controlling, but if you learn that you’ll be able to create panels for a lot more hardware, especially those older synthesizers from the 80s and early 90s (all the Yamah DX series, Roland’s Juno series and loads of others).

First thing to do is to get the MIDI specification for your hardware, without that you won’t get anywhere. Get the manual read it, try to understand it. A lot of older hardware has some very bad documentation, some of them are poorly scanned PDFs, but even if you get a nice and well formatted document, the content is bad. There is no standard here, each company had it’s own idea on how to implement MIDI, what’s even worse is the idea changed from device to device. Any hardware that let’s you dump it’s memory contents either as programs or as any custom data (for example waveforms) uses System Exclusive messages to do that. So before you go on, read about what that exactly is, the best place to start is “The MIDI Specification”, Very often those manuals will talk about Bits and Bytes, more often about “Least Significant” and “Most Significant” parts of a byte, about splitting bytes, about checksums, about encoding ASCII characters and other weird ass computer stuff you might not know. Learn this stuff if you want to continue, if you have some basic knowledge of how computers work what’s a byte and how many bits there are it should be very easy, but if you never heard of all that stuff, reading about it first will help you a lot. It might be boring and it’s mostly maths but it will allow you to understand the manual and implement it. On the bottom of this page you’ll find some more links, use them, please.

Sometimes there are some custom editors built for synthesizers, most of the time you’ll want your panel because the available editor are old, crash, not run at all, or run only on Win 3.11 or worse on Atari. But even this old software can help you, if you can get it to run. Run it in an emulated environment or a VM, use a Virtual MIDI cable. Do anything that will let you catch the MIDI data flowing between this old program and your hardware. You’ll be able to compare your findings with what the program has implemented. Look at the bottom of the page for some interesting links on this subject.

Once we got the manual, we understood it, we can get to work.

I recommend starting with a layout. Maybe draw it on a piece of paper or in “Paint”. The idea is not to copy the layout of your synthesizer on the computer screen, why would you? Ctrlr was crated to get access to parameters hidden under layers of menus displayed on small 2×20 LCDs with no backlight, often operated using plastic membrane buttons. So try to make your layout efficient, so you get access to all parameters quickly, if there is too much stuff (some of the hardware out there has over a 100 or even over 1000 parameters), plan to put some of the stuff inside Tabs or on “Layers” that you will later make visible to the user. Group the parameters in some clever way “Oscillator 1”, “Filter”, “Filter Envelope”. Spend time to name your parameters, but keep in mind the plugin hosts that will later host your panel might “cut” your names, so try to keep them as short as possible and as descriptive as possible (i know it’s hard). I try to make names appear as paths to a parameter, for example:

the Evolver has sections of parameters: “Synthesizer”, “Global”, “Sequencer”, all my parameters will have a prefix to the section, then they’ll reflect the subsection and then name of the parameter itself. Since i try to keep those names below 8 characters (this is a limitation of the VST specification, most of VST hosts don’t really respect that limit but some do, so you decide on witch team you want to be). For “Cutoff” that is in subsection “Filter” that’s in the section “Synthesizer” i’d do, “srFltCut”, for step 1 of sequencer 1 (there are 4) i’d do “sq1Step1” etc.

It’s up to you, but remember that others might want to use it, and that memories fade and you will forget what you meant in 2 years. IMPORTANT this is your panel do whatever you want, as long as it suits your needs, all those suggestions here are very subjective.

Once you get the layout, there is one important thing to consider, will you need some custom logic in your panel. AS i mentioned above any information exchange with the device thats called “memory dump”,”sysex dump”,”bulk dump”,”program dump” involves using System Exclusive messages and custom ways of processing it. One thing that the MIDI specification does not specify is how this exchange should happen. That left a giant hole of possibilities to vendors. There is no single program that can implement all those ways. Programs like “Sound Diver” or “Sound Quest MIDI” actualy have big (in terms of amount not disk space they use) databases of additional modules, addons, plugins and scripts that do all that (if you buy the Sound Quest program you actualy get access to it via a FTP server), this is the power of those programs someone already implemented this logic for you. if you want your panel ti implement all the features your MIDI device has, and one of those features is stroing programs on your computer, you will have to at some point write a piece of Lua code to handle this. I mention this here because it might be hard for people who never wrote a single line of code to start writing code. What i can say is that i tried to make this as simple as possible, understanding your device and having the basics of computer theory will help. You don’t need to be a programmer to write this. Lua is a simple language, it’s called a “scripting” language because you don’t need a special “compiler” “debugger” “IDE” or any of that nonsense, all you need is the Ctrlr binary and some patience. So just remember if you want program dumps, Ctrlr will need your assistance in form of a script.

Let’s start the actual work. First we’ll create the “Oscillator” sub section section of the “Synthesizer” section. When we look at the manual we get a list of parameters for oscillators (in the Evolver manual this is the program parameter data), the parameters are:

This list helps us see how we should place our components. When we look at the value range for each of the parameters we should decide what UI element will be best suited for this parameter. Large linear values are good for Sliders (oscillator frequency, oscillator level, fine tune). Things that longer descriptions and have just a few values are good for Combos or ListBoxes (oscillator shape). All boolean (true/false) values are best suited for ToggleButtons.

Let’s create the oscillator 1 controls (components), for now we’ll just place the on the Panel area. Right click on the panel area somewhere, select and “Sliders”->”uiSlider”, a new rotary knob will appear on the Panel area, drag it around, resize it do what you like with it.

You will also notice that when you select that slider the set of properties to edit on the Property panel changes, you will see a set of properties that apply to the slider itself, for now scroll down the Property panel and change some colors for this new slider, you will get the basic idea of how the Property panel works. For the Oscillator 1 let’s create 4 sliders and one Combo (uiCombo can be found under Buttons in the menu). Here is the relevant properties we want to set to those new components:

Slider->Oscillator Frequency

Slider->Oscillator Fine Tune

Slider->PW

Slider->Level

Combo->Shape

We’ll get back to the MIDI stuff a bit later, for now let’s focus on getting our sliders in place and where we want them. Let’s try to group our components, create a new uiGroup component “Groups and views”->uiGroup. Resize it so it can fit all our Oscillator components, give it some useful properties like the Text, the background colors etc. Once there, drag each of the Oscillator components onto the uiGroup, you will notice that the dragged component will “jump into” the group component, it will become a “child” component of the group, now moving the group will move all it’s children, you will also get an option to copy the group and it’s contents and later paste it anywhere on the Panel.

Let’s do that now, we have 4 oscillators but they share properties in pairs (oscillators 1 and 2 are analog while 3 and 4 are digital). So let’s right click on the group and select “Copy with children”, it does exactly that, it copies the group component and it’t contents. Now let’s pick a position somewhere below the already existing group, right click and “Paste”. Now we have a copy of the first Oscillator group. Select one of the components in the new group (the one below), notice how the modulator names have changed, they had to, those names should be unique within a panel, Ctrlr will just add numbers to the end of the name. Rename your components to match the Oscillator to controls, keep in mind that the System Exclusive formulas must also change since the Oscillator 2 controls have different parameter numbers inside Evolver. Here is a list for Oscillator 2:

Slider->Oscillator Frequency

Slider->Oscillator Fine Tune

Slider->PW

Slider->Level

Combo->Shape

Let’s change the display name for the group so it looks nice. In the end we should be looking at something like this:

A word about static Components (modulators). Some of the elements (uiGroup, uiTabs, uiLabel, uiImage and others) you add to your panel are considered static, they have a special property set “Modulator does not react to value changes”, and have less properties in the “Modulator” section, also no MIDI section at all. Those components are used only for displaying stuff on the screen, they help to organize your editor. Name those components in a more “human” way, since they won’t be visible to Plugin Hosts, those names can be very long and more descriptive.

We have some components on the screen, we can see them place them, but what if we want to verify one of the property for all the components. For example we quickly want to see all the System Exclusive formulas for all components on our panel. We can do that by clicking each one sure, but it will take time. There is a utility view for a panel called “Modulator List”, you can view it from the MenuBar->Panel menu, do that now. A window with lots of columns should appear, you can adjust what columns you want to see in the Modulator List’s Menu Bar, under View->Visible columns. Columns are named after raw IDs we talked about earlier, this will help with sorting columns and takes less space on the screen. Please notice that when you select a modulator/component on the list, the same selection is reflected on the panel, this might be helpful if you mi-placed your component, it went off the screen or is hiding under some other component, you can use that list to locate those “lost” components.

Okay so we have our 2 analog oscillators in place, let’s jump to the 2 digital oscillators, the controls will be slightly different but similar. We can copy one of the already existing groups and adjust it to fit the new digital oscillator, or we can create it from scratch. I chose to create it from scratch to give it a different look. What’s different here ? First of all the shape is a linear value of 0-128 so no need for a combo, just a slider. But we have 3 new parameters that are specific to digital oscillators, here is how we’ll create them: FM – Toggle Button, Ring Mod – Toggle Button, Shape Mod – Combo.

But wait we missed one parameter for each oscillator, the Glide parameter and there are two oscillator specific options for the analog oscillators, the Sync and Slop parameters. Sync is between oscillators 1 and 2 the Slop is a global parameter, all 4 oscillators have a Glide control, we need to add that to the analog ones and include that in the digital oscillators. This is a good place to think about the layout, since the Sync and Slop parameters are only linked to Oscillators but do not affect any single one of them, we need to make sure we can see that on the panel.

For grouping the oscillators together we’ll use a parent group for those Oscillator groups, things to remember when working with groups:

After some work, re-colouring, resizing, re-positioning, assigning names, grouping, setting SysEx formulas, this is what you should have more or less, choose your colors choose your shapes and your placements, you should have the same MIDI SysEx formulas set though (that’s written in the manual):

If you want to verify your data, ctrlr_tutorial_modulator_list_1, so you can copy/paste stuff (you can always do that in the Modulator List window).

IMPORTANT, when changing SysEx formulas using the Modulator List or the normal Property panel, remember to set the type first, set it to SysEx then type in the formulas.

HINT, you can multi select components on the panel using the CTRL+click combination, the Property panel will display all common properties for the selected components, their MIDI and modulator properties (the properties they share, any property that does not belong to ALL selected components will not be shown), you can then change any property in bulk.

At this point we’ll end the editing part of the tutorial, now you know how to add stuff to the panel, how to edit it, how to group it. Experiment with other components, see how they work, change them. The idea is always the same.

We need to dig a bit deeper into that MIDI stuff we used in the panel but didn’t payed a lot of attention to. I’ll try to explain this on an example, we’ll use the Glide parameter for Oscillator 1 for this. First let’s look at the manual what it says about this parameter, go to page 47 of the PDF manual, to the section called “Sysex Exclusive Messages”

Let’s have a closer look at the table titled: “Program Parameters”, it’s a nice table, trust me. Most of the time the manufacturers of MIDI hardware are not that nice and their description of System Exclusive Data is bad or worse then bad, sometimes it’s not even there at all. Sometimes the description will be very good but so complex you simply won’t get it the first time (i think the most over complicated SysEx implementation that had to be written by someone on some serious drugs is the Casio CZ series MIDI implementation). But back to our table, we get this set of Bits called “Status” and a Description, we need to translate this to a SysEx Formula that fits into Ctrlr. How to do this ? First of all we need to convert those bits into Hexadecimal values, this will make things a bit more readable, you can use any calculator for this, but Ctrlr has one built in, just go to “Window->MIDI Calculator“, and one will appear. Now type in those bits from the table in to the “Binary” input, exactly as their written, replace any “v” or “x” or “y” or anything that’s not “0-9” and “A-F” with zeros, change the combo in the calculator to: “HEX String format“.

Now our bits appear a bit closer to what we used in our “SysEx formula” property before. Though not exactly the same we can try to decode it now, the data in Hexadecimal we got is:

f0 01 20 01 01 00 00 00 f7

Ok let’s start at the beginning. This magic string is a representation of a piece of computer memory, 9 bytes each byte being represented by a set of 8 bits we typed in from the manual (zeros and ones). The representation is written in base 16 notation also known as HEXADECIMAL.If you don’t understand what’s all this about read about it, you need to know this math stuff to get further and if you want to understand what’s happening. I’ll assume you know the difference between base 16 (hexadecimal), base 10 (decimal), base 2 (binary) notations, i’ll also assume you can use a calculator to convert between those types (when in doubt use the Windows calculator in “Programmer” mode). What is important here and is different then your usual 8bit per byte mumbo jumbo, is that MIDI uses only 7bits per byte, that’s how someone designed it in the eighties (that someone waas Dave Smith). So one MIDI byte is 7bits, one computer byte is 8bits. What does it mean for us ? We’ll we get one big limitation in MIDI we can’t send more then 128 values in one byte, if we used all 8bits we could send 256 values, but since we got only 7 that’s 2^7 and that’s 128. Google this a bit more if you are unsure what this means, i don’t know if writing more will explain it better, use a calculator try to convert some values, try below 127 and above see what you get from that.

Let’s go through our data from the MIDI Calculator byte by byte

Here we’ll discuss how big numbers are sent using MIDI messages. First of all there are many ways to do that, i’ll describe the most common two i know of. Knowing the MIDI world there are others, if you find them you’re on your own i’m afraid, all i can do is help you on the forums.

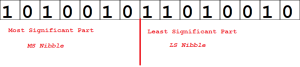

One way of sending large numbers in MIDI that’s well documented and considered a standard is the method used for RPN and NRPN messages. Those messages can carry a number in the range of 0-16364, that’s 14bits of data, in two 7bit bytes, sent in two separate messages. The idea is simple really, there is a lot of maths involved, but in essence you take your number, represent it as 14bits take the first 7 send it, take the other 7 and send it. Those 7bit parts of a 14bit number are called “Least significant bits” for the first 7 bits, and “Most significant bits” for the second part, remember that we read bits right to left. So we start with Least and go to Most significant parts, this is the same with bits in a byte, the lowest bit (rightmost) it the least significant, the highest is the most significant.

For splitting a 14bit messages into 7bit parts.

For splitting a 14bit messages into 7bit parts.

So this is the most common way, take a 14bit value split it in two 7bit values and send it in two messages, in case of NRPN and RPN the messages used are Continues Controller messages aka CC. It needs to be said that not only the value is 14bits but the controller number is 14bits, so in order to send a value change for one NRPN or RPN parameter you need to generate 4 CC messages (it’s all explained in the MIDI Specification under RPN messages).

Sometimes there is no need for 14bits, sometimes 8bits is enough (that’s 256 values), so instead of splitting a 14bit value we split a 8bit value, now we can use the same maths and rules as for NRPN and RPN messages, and that would be fine. Sometimes though, the split happens at 4bits, that’s an 8bit message split into two 4bit values, this works too but it generates a different set of values. This 4bit split is used in the Evolver Desktop synthesizer.

These are the two most commonly used methods of encoding large numbers into MIDI messages, there are others i imagine, but so far those two were enough.

Now knowing this, we look inside Ctrlr, the property “SysEx formula looks like this”:

Two things about that property.

I’ll explain all the menu entries here:

Insert vriable:

Insert static:

Checksums tN t=type N=num bytes to count

All checksums have the same format, tN, where the “t” token indicates the type of checksum to calculate, and N is a number that tells Ctrlr how many bytes to before the checksum byte to include in the checksum algorithm (a checksum is a number that verifies if the reception of data is correct, it needs some data to be calculated, so the N number tells Ctrlr how much data to read)

Global Variable

So now we know how to handle our bytes and how to do that in Ctrlr, so our formula

f0 01 20 01 01 00 00 00 f7

Can now be set with understanding, we need to replace the “Parameter value” part of the message with a DSI specific 4bit split, since in Ctrlr we use “ls” and “ms” as tokens for that split, we write our formula for the first paramter from the manual as:

f0 01 20 01 01 00 ls ms f7

This is what we did when adding our sliders to the panel.

Now we know how and why. Armed with that knowledge we can continue adding new controls to our panel. We know how to set the formulas for all of them, choosing the right graphical representation is a matter of taste and choice. Pick your own ones, and continue with your panel. There is one thing that we still need to know, nowhere in what we already found out was there a negative number like -20, and as we can see in the manual (for that any almost any other MIDI device), there are parameters that have negative values (like panning or tuning), or at least the description of the parameter indicates that this parameter is represented by a range of values bot positive and negative (that does not change the amount of values we need to send via MIDI, -63 – 63 is the same amount of values as 0 – 127, it’s always 128 values we need to send, remember that). Let’s talk some more about negative values.

MIDI Specification and other interesting MIDI documents – described but “jglatt”

MIDI Specification – the official document

Binary Hexadecimal tutorial (1) – might help you understand all the HEX DEC BIN stuff

Binary Hexadecimal tutorial (1) – might help you understand all the HEX DEC BIN stuff (some more information on most and least significant parts)

MIDI OX the MIDI swiss army knife and MIDI Yoke the virtual MIDI cable (Window only)

Free virtual MIDI cable that works on Windows 64bit

A large list of MIDI software, a lot of editors and other useful stuff

This is a simple Lua method for panels that have a broken mouse cursor for some or all components.

The mouse cursor disappears when mouse is over it. Just paste this method to the console and run it (that means, paste this code, press enter, this will compile the code, then remove the input from the console and run the method by typing “fixMouseCursor()” and pressing enter)

function fixMouseCursor()

-- Your method code here

for i=0,panel:getNumModulators()-1 do

m = panel:getModulatorByIndex(i)

if m ~= nil then

c = m:getComponent()

if c ~= nil then

c:setProperty("componentMouseCursor", 2,false)

end

end

end

end

Expression are used to calculate values that Ctrlr sends to the device, and when they return in form of MIDI messages.

To understand expressions we first need to know 2 things:

1. Modulator lifetime

2. Expressions overview

3. Expression functions

The lifetime of a modulator, when we look at it as an object that links a parameter in a synthesizer can be split in two “sending” and “receiving”.

Remember, a modulator can have many other functions, but this one is the primary function. A modulator sends numeric values and receives them. In MIDI it’s all about numbers, yes you can transmit patch names, waveform data, but it’s all numbers. What is important it’s always positive numbers 0 – N (n is not really defined, you should define it for every modulator). The number sent by the modulator is actually held in an array, the array is linear, it’s size is N. When you change a component, it tells the modulator about the change, it tells it what new value it should have, let’s say x. When modulator is told that it’s new value is now x, it first looks up the number that’s at position x in the array. If you set up the max/min values correctly for a modulator the x will always be inside the array. Once the modulator has the number it does a bit of processing on it. Few things happen with that number

1) a special Lua method is called

2) an expression is processed if it exists

3) the number is inserted into the MIDI message

Once all that is done a MIDI message is produced and sent to the device.

When a MIDI message is received by Ctrlr it goes through a lot of checks before it reaches the modulator it’s intended for. There is the whole subject of how the message is matched but we won’t discuss this here, we’ll assume that Ctrlr did it’s job and found the modulator it should deliver the message to. So the modulator gets the MIDI message and a few things happen

1) a numeric value is extracted from the MIDI message

2) an expression is processed if it exists

3) a special Lua method is called

Once the processing finishes, the numeric value received is passed to:

– the associated component (if one exists)

– the plugin host (if Ctrlr is in plugin mode, that will be the actual Host application in standalone mode Ctrlr simulates a Host, so this always happens)

There are 2 types of expressions, “forward” and “reverse”, “forward points to the “Sending” state of the modulator and the “reverse” to the receiving state of the modulator (as described in point 1)

In Ctrlr an expression is a mathematical function with one argument. It does not use any specific programming language to describe the function. It uses a custom parser included in the JUCE library (more information here). ou can use all the basic math operations “+, -, *, /” you can (and often should) use parentheses to group your maths. Along with the basic operation there are some custom functions you can use to get more out of expressions. Also there are variables in expressions, those variables are named and reflect the state of the panel.

We’ll start with “forward” expressions.

A basic expression is a constant for example:

13

That is a valid expression, this would cause any modulator to send the value 13 no matter what it’s state was.

By default the expression is defined as

modulatorValue

This defaults to the current value of the modulator as described by it’s properties and the properties of a component attached to it. No logic is applied, no functions executed.

We can easily combine the two:

modulatorValue+13

This will cause the modulator to send it’s value with 13 added to it always. How is this useful ?

Let’s take the panning example (we’ll assume that we are dealing with MIDI CC messages), we have a parameter that has a range of visible values from -32 to 32 while using range of MIDI values 0 to 64, we need to create a slider that will represent those visible values in the user interface (in form of a Slider) while sending the correct range of numeric MIDI values ranging in 0 to 63 (64 values).

First we’ll set our slider to have it’s minimum value of -32 and maximum value of 31 (why not 32?, well you get 32 values from a numeric range of 0-31, but it might be different with every device), that’s the easy part. With that range applied, the slider will spit out bogus data when setting values from -32 to -1. Once the slider reaches 0 it will start to behave correctly, but it will actually send data for the “left” part of the stereo spectrum, never reaching the “right” (we assume -32:-1 is left and 1:31 is right, 0 is center). Let’s change the expression to

modulatorValue + 32

Now the modulator will add 32 to all it’s values so -32 becomes 0, -31 becomes 1, 0 is 32 and 31 is 63. This is what we wanted. Our “sending” life cycle of our modulator is set and working.

Let’s move over to the “reverse” part, most of the time this part will require some knowledge of MIDI. Since we are dealing with MIDI CC and we are not dealing with numbers larger then 127 we’re safe. We assume that our MIDI device will respond with CC messages that have value 0 – 63. Let’s change our “reverse” expression to

midiValue - 32

What happens now ? When a modulator receives a MIDI message that’s intended for it. It will take it’s numeric value (in some cases the actual value may be the controller number if defined, or some other part of the message) and process the expressions, that is for any value that it receives it will subtract 32 and the result of the subtraction will be passes to the modulator, making it the new value. One very important thing in the reverse expressions is that they happen on the MIDI thread (or the Audio thread if the MIDI messages are coming from the Plugin Host), so keep them simple where possible.

To do more complex maths, Ctrlr provides some basic math functions and some logic-like-functions (basic if statements) that can help you. Also there are some constants that represent certain values in the panel, those can help you make your modulator values depend on the panel state. Some constants are not available in both forward and reverse expressions. Here is a list:

Constants:

modulatorValue : The current linear value of the modulator, this is the index of the array of values, it’s always positive.modulatorMappedValue : The current mapped value in case of components that have mappings. This might be negative.modulatorMax : The maximum value the modulator can have (non mapped)modulatorMin : The minimum value the modulator can have (non mapped)modulatorMappedMax : the maximum value the modulator can have (mapped)modulatorMappedMin : the maximum value the modulator can have (mapped)vstIndex : The VST/AU index of the paramter as seen by the host programmidiValue : The current value stored in the MIDI MESSAGE assosiated with the modulator.midiNumber : The number of the MIDI MESSAGE controller if applicableFunctions:

ceil(x) : Returns the smallest integral value of the parameterabs(x) : Returns the absolute value of the parameterfloor(x) : Returns the largest integral value that is not greater than the parametermod(a,b) : divides two numbers and returns the result of the MODULO operation “%”. Examples 10 % 3 = 1, 0 % 5 = 0; 30 % 6 = 0; 32 % 5 = 2 For more info http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Modulo_operationfmod(numerator,denominator) : Returns the floating-point remainder of the two parameters passed inpow(a,b) : Returns the first parameter raised to the power of the second (a^b)gte(a,b,retTrue,retFalse) : Return the larger or equal of the two passed parameters (a >= b). For examplegte (modulatorValue, 0, modulatorValue, 128 - modulatorValue) will return modulatorValue if modulatorValue is greater then 0 and (128 – modulatorValue) if it is less then zerogt(a,b,retTrue,retFalse) : Same as gte but greater then without the equal sign (a > b)lt(a,b,retTrue,retFalse) : Same as gte but less then (a < b)lte(a,b,retTrue,retFalse): Same as gte but less then or equal (a <= b)eq(a,b,retTrue,retFalse) : Equals sign true if (a == b)max(a,b) : Returns the bigger of two parameters.min(a,b) : Returns the smaller of two parameters.getBitRangeAsInt (value, startBit, numBits) : Get’s a number of bits (numBits) starting at position startBit as an Integer and returns that integer.setBitRangeAsInt (value, startBit, numBits, valueToSet) :clearBit (value, bitToClear) : Clears a bit at position bitToClear in the value and return that modified value.isBitSet (value, bitPosition) : Return true if a bit at position bitPosition in value is set, false otherwise.setBit (value, bitToSet) : Set’s one bit in an integer at position (bitToSet) and return the modified value with the bit set.setGlobal (globalIndex, newValueToSet) : This set’s the value of one of the global variables in the panel, and returns that set value so the expression can continue.This is the Yamaha TX81Z panel, with graphics by Lime.

It can edit all parameters available in TX81Z (except Reverb Amount, can’t find what sysex it uses in the MIDI specs). This is a bugfix

release that should work with the latest Ctrlr binary (some SysEx tokens were changed from “XX” to “xx” yes SysEx tokens are case sensitive)

Download Size: 633.5 KB Downloads: 11,225